Unsettled in Istasyon

Mardin, Turkey

Essays by Janine di Giovanni

Mardin, 30 kilometres from the Syrian border in Southeastern Turkey, is a city whose roots stretch back to the Bronze Age. It was once part of Assyria, and one of the oldest cities in what was once known as Mesopotamia. It was a gathering place for four religions: Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Yazidism.

When the Syrian crisis started a decade ago, nearly 3.6 million civilians fleeing the country crossed the border to Turkey and found their way to Mardin. They mainly settled in this ancient, terraced city in the neighbourhood of Istasyon. Today it is estimated that there are some 88,000 Syrian refugees in Mardin.

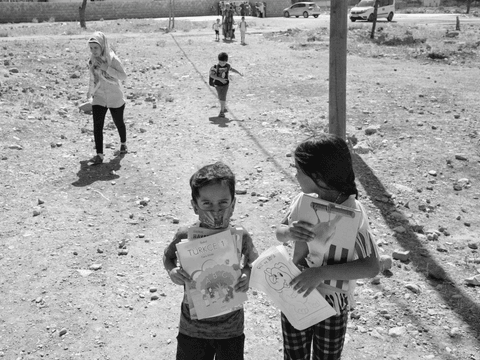

The Syrians adapted from the trauma of exile from their homeland and learned to live side by side with the Turkish people. They learned the language, worked alongside Turkish citizens, and enrolled their children in local schools.

COVID-19, which came to Mardin in March 2020, threatened to halt this progress. Most educational institutions immediately closed down. The five-month lockdown that followed created a sense of deep isolation for the children of Istasyon, compounded with the fear of the virus and their past trauma of displacement.

One woman, Roshan, said that the effect of COVID-19 was extreme.

“I feel far away from everyone now. I’m even afraid of my neighbours. What if they get sick?”

She feared contagion, but also feared being unsettled in a new land.

The journey of a refugee settling into their host country is already wrought with displacement, loneliness and isolation: COVID-19 made that more arduous.

For the children, their new schools were more than just a place to learn – they were also a source of socialization and sense of belonging. There, they met Turkish children, and learned their language. Even if they went home to the Syrian Arab Republic someday, they took solace in shared Turkish community life.

What the children missed most due to the pandemic was their friends and simple, joyful playing, even if such play was merely running across the railway tracks. Friendship, especially in the Syrian settlements and communities, is vital to their development.

Retreating into their close-knit Syrian family lives meant that when schools did open gradually in September 2020 – but only for students up to first grade – it was harder for some children to integrate.

“He has been spending his days with me for months,” the mother of one small boy, Enes, said. “He doesn’t want to leave me anymore.” Berevan, 30, another mother, said she regretted that her 6-year-old son, Shakir, couldn’t go to preschool, which he was due to start this year. She worried about the effect the lockdown was having on children.

“It’s okay for us, but hard for the kids,” she said. “Because of COVID-19, I never let them go outside.”

Many of the children were born after their families fled the Syrian Arab Republic: They speak Turkish and were slowly assimilating into the culture before the pandemic. But some of the children, confined at home, forgot how to speak their new language. The Turkish Ministry of Education offered online services, but many of the families had limited or no access to the internet and often did not own smartphones, computers or tablets.

Zehra, 9, who is in Grade 3, could not find a phone or computer, so she did not go back to school. Her mother, Henuf, 44, said despite her waning language abilities, she was hopeful Zehra would pick it up once life resumed.

Norma, 13, is one of seven children living in Istasyon with her family. The lack of access to education during the pandemic forced families like Norma’s into new precarious situations. Due to economic pressure, two of Norma's elder sisters were pushed into engagement. Other siblings had to leave school entirely to support the family. But Norma has persevered. She was the only one in her family who was able to continue her education, diligently completing her lessons through the small screen of her father's smartphone. She said she wants to become a police officer when she grows up “because people respect them.”

COVID-19 forced families of Istasyon to adapt – taking irregular jobs, and compelling children to assist at home. But forced adaptation often emboldens community ties.

Halit, 47, and Souda, 55, settled into their temporary life in Istasyon for seven years before COVID-19 descended. Now Halit collects and sells garbage, assisted by two sons who should be in school. He earns about $12 a month. Souda contracted COVID-19 in July; she was ill for more than a month. But she learned the true meaning of community: Souda says while she was quarantined and ill, someone – an unknown and compassionate neighbour – left a bag of food outside their door every night for six weeks. Souda never knew who her mysterious helper was.

It has been more than a year since the virus first arrived in Turkey. While the unease of a foreign land continues to bring new challenges, residents of Istasyon continue to look out for each other, inspired by the spirit of hope, imagination and the dreams of their children.

About UNICEF’s work for every child

In Mardin and beyond, COVID-19 threatens to exacerbate the learning crisis – the number of children aged 10 years who cannot read and understand a simple story – by 10 per cent. Globally, more than 90 per cent of students were out of school at the peak of COVID-19. Many may never return, including in Turkey.

UNICEF is committed to getting children back to in-person learning as soon as possible and ensuring they have the services they need to readjust and catch up after the pandemic. In Turkey, UNICEF and Ministry of National Education (MoNE) launched a nationwide “Back to School campaign” focused on scaling up access to safe and quality education for all children and youth. Learn more about how we’re helping here.