The School of Stars

Lesbos, Greece

Essays by Janine di Giovanni

Moria Reception and Identification Centre, on the Greek island of Lesbos, was built to accommodate only 2,200 people. By 2018, it had become the largest camp in Europe for refugees and migrants – its population swelling to over 18,000 men, women and children. Many residents expected to be in Moria for only a few weeks or months. Instead, families routinely wait over a year for their asylum claims to be processed.

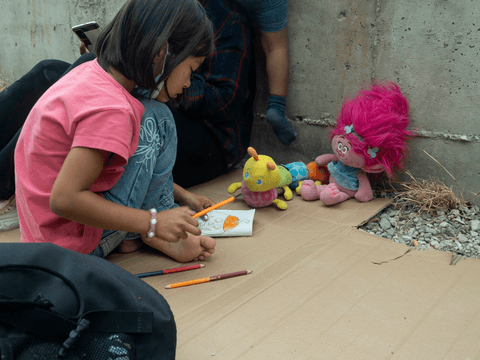

Life in Moria is a challenge, a testament to people's resilience and endurance. Masha, 8, migrated to Moria in 2019 from Iran with her family. She told Magnum photographer Enri Canaj her story of “walking in pain and fear” on an arduous trek from Turkey.

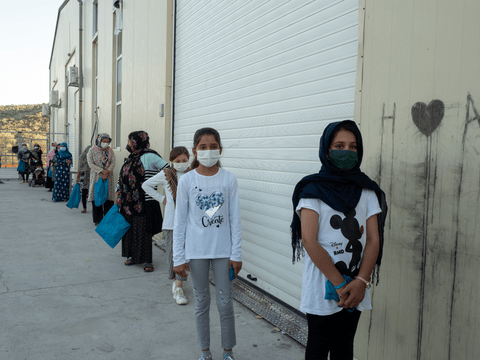

In Moria, families live in tents and must wait in line for toilets and showers with cold water. Access to drinking water is a perennial challenge in the camp. Residents walk over one kilometre to the nearest town to get water. Children grow up quickly. They become responsible early on: waiting in food collection lines; collecting empty bottles from garbage piles; and trading the empty bottles for new bottles of water to carry back to their families’ tents.

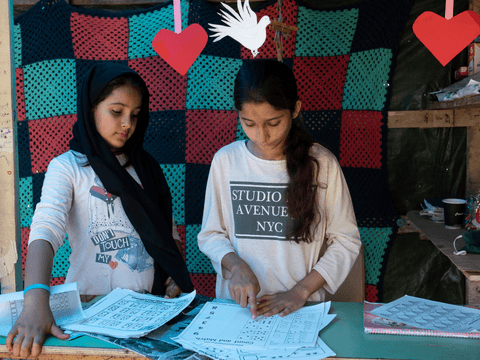

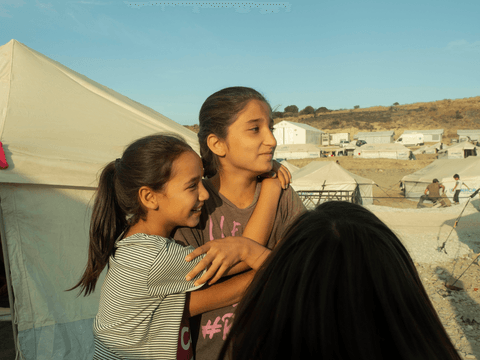

When COVID-19 reached Moria, aid organizations had to scale back their operations to an emergency-only basis, and authorities heavily restricted the movement of people in and out of the camp. With few health and sanitation interventions, residents fashioned their own hand-washing stations to lower their risk of contracting the virus. With schools temporarily closed, and no access to online learning systems, the children of Moria were left without the ability to continue their education. Manija, 13, and Atefe, 11, migrants with Afghan roots, had time on their hands and a passion for education. They saw an information gap.

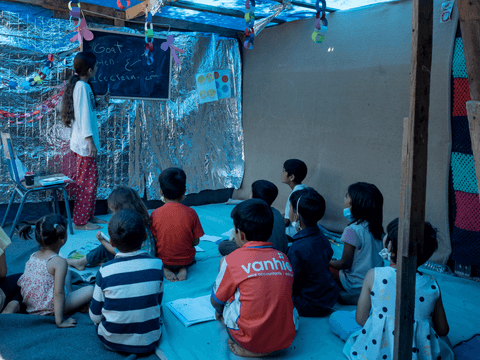

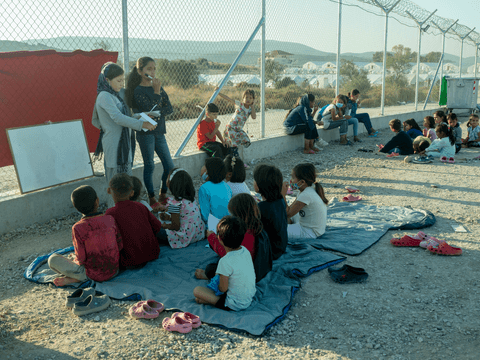

With fewer activities for children in the camps during lockdown, the two set up their own “School of Stars.” The school initially began as a role play between just Manija and Atefe. Soon parents, eager for their children to have something to do and continue learning, dropped off their children for lessons and much-needed socialization with other children.

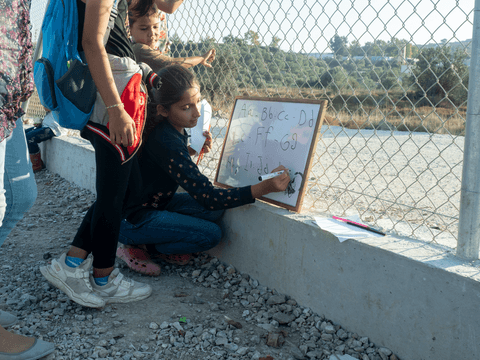

Nearly every afternoon for roughly four hours per day, Manija and Atefe taught English and Persian to over 20 children. Beyond teaching both English and Persian alphabets and vocabulary, they taught the young School of Stars attendees other vital skills: how to ‘treat’ the camp water, how to wash their hands, and how to sanitize their families’ tents with the limited resources available in the camp.

The school also became in many ways a site of psychosocial support and provided a sense of belonging. Manija and Atefe intuitively understood the emotional needs of their students. They talked to them openly about their happiness and well-being. “Teaching is my passion,” Manija says. “In the class we provide masks to every student, we suggest they wash their hands, and we sanitize.”

“I want to grow up so I can be useful for the community,” Manija says.

In an uncertain time, the School of the Stars brought pride and joy, and gave these two young teachers a goal: Both want to become professional teachers one day.

But on 8 September 2020, the school faced its first major challenge. That night, a large fire engulfed the camp, destroying the facilities, decimating informal accommodation structures in the olive groves surrounding the camp, and displacing thousands of residents.

Families who had struggled to make their shelters now had to sleep outside, with only the trees for cover. Most went several days without food or extra clothes. Many were homeless for weeks as they waited to move into a new camp. Greek authorities, seeking to curb the spread of COVID-19 amidst this mass displacement, conducted rapid testing of asylum-seekers entering the new facility. Those who tested positive for COVID-19 were placed, with their children, in quarantine.

Two days after the fire, Masha and her family waited for relief along the side of the road with all their possessions in tow. Masha recalled vivid memories of the fire: people screaming and running from their tents. Authorities expanded another camp, Kara Tepe, to accommodate those displaced from Moria. However, the camp lacks many of the facilities of Moria, including toilets and showers. At night, the girls wear nappies, avoiding safety concerns outside their tents.

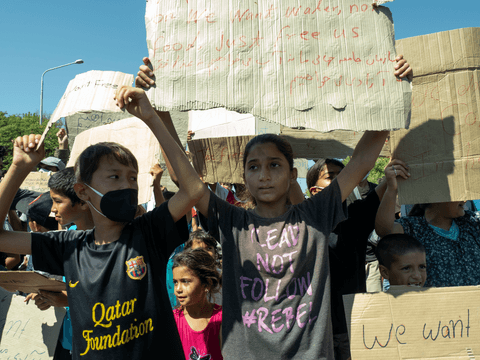

Despite concerns over the spread of COVID-19, medical masks were not available in the camp until September 2020, and even then, there was a shortage. Residents made their own masks and often reused the single-use masks that the camp finally did provide. Thousands of refugees protested the conditions they endured in the days after the fire, Manija among them.

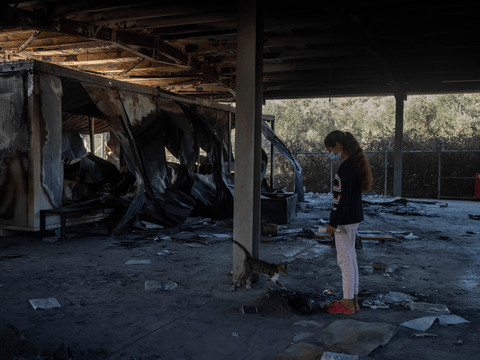

Weeks after the fire, Manija returned to Moria to assess the damage to the tent that housed the School of Stars. The young woman searched for school supplies that may have survived the blaze. She was determined to continue with the School of Stars. The fire would not set back her goals.

Under the COVID-19 lockdown, there were no organized activities for children at Kara Tepe camp. Undaunted, Manija and Atefe opened their School of Stars in the new camp. With no defined space, they taught lessons outside and cancelled classes on days of poor weather.

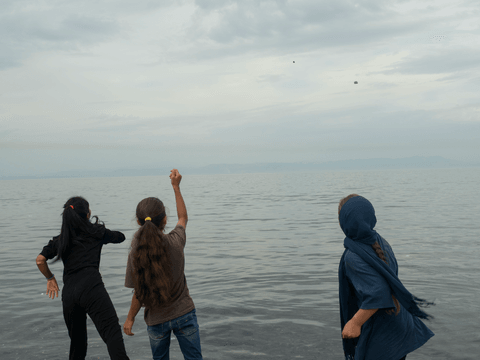

Despite their perseverance, the damage of the fire was far reaching. It displaced and deprived many children of the friends they had made in Moria, and eroded their optimism of a better life beyond the camp. Masha’s older sister, Atena, 10, said, “I don’t like life in the new camp. My friends live far from my tent and I don’t see them every day...

“The only good thing that has happened to me are my new friends; they are my best friends now.”

The children have found respite skipping rocks across the turquoise Aegean Sea and spending time with friends. But they remain hungry to learn more. Manija has since resettled in Germany, her friends still in Lesbos long to expand their opportunities beyond the island. Masha, still in Lesbos, continues to crave more.

“I dream [that] after Lesbos, life will be good to me.”

About UNICEF’s work for every child

Refugee girls are among those most affected by the impact of COVID-19. Even before the pandemic, just 31 per cent of refugee students attended secondary school. Based on UNHCR data, the Malala Fund has estimated that half of all refugee girls in secondary school will not return when classrooms reopen.

UNICEF is committed to ensuring children like Manija, Atefe and Masha have access to quality learning and the services they need to readjust and catch up after the pandemic. Learn more about how we’re helping here.