Waiting for Nothing

Itacaré, Brazil

Essays by Janine di Giovanni

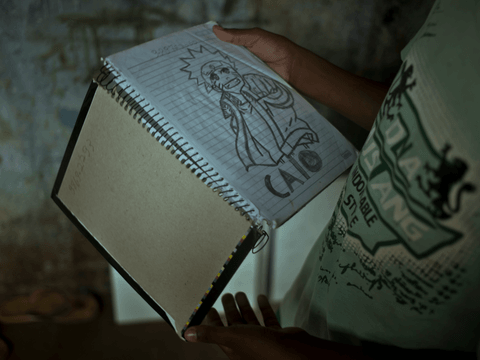

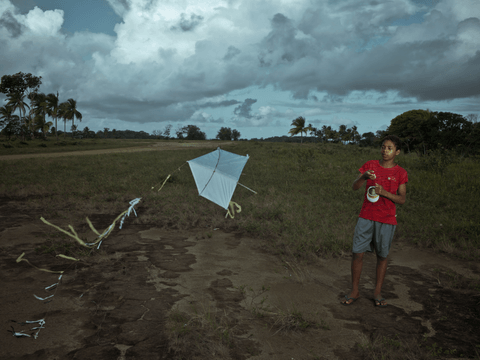

Like so many children impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, 12-year-old Caio in Itacaré, Brazil has feelings of being lonely and directionless.

Even before COVID-19, Caio struggled in school. He needed support to help him become more curious, more engaged with his schoolwork.

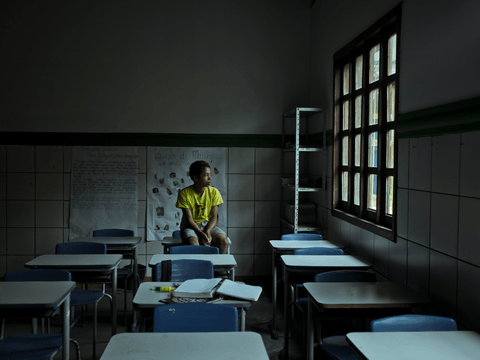

At first, he was relieved by the school closures. Caio was bored with school and had been held back in the fifth grade twice. He was easily distracted in class and made excuses not to do his homework. Caio thought his teachers didn’t like him, so he played the class clown. Jokes and pranks led to him being expelled.

COVID-19 hit Brazil hard. As of August 2021, more than 560,000 people in Brazil have died and many fear a worsening crisis as more people contract the virus. The health-care system, already under pressure, has become severely strained.

In the midst of the pandemic, Caio navigates daily life in a favela in Itacaré, a coastal town in the state of Bahía. On his long walks through the favela, he has a mask in his pocket, ready to be put on in case the police appear. The fine for violation of the mask mandate is about 10 per cent of his mother’s hard-earned monthly income.

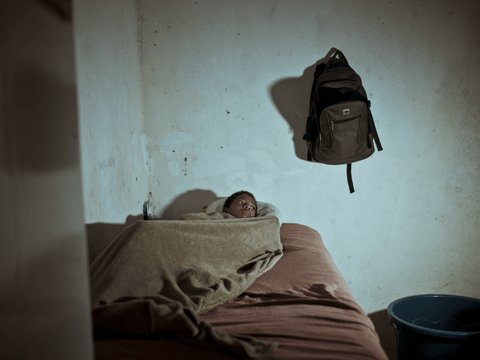

Caio’s mother, Simone, works 12-hour days as a housekeeper for a wealthy family to support her three children. They live paycheck to paycheck. Simone feels guilty and disappointed by her inability to spend more time with her children, but sees no other choice but to go to work. Caio has become more self-sufficient. When he wakes up, he makes himself a breakfast of bread, margarine and coffee with powdered milk. The day ahead of him, which Caio enjoys spending outdoors.

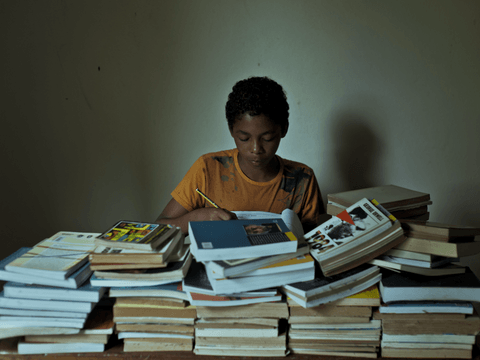

Even if he did not find learning stimulating, Caio did enjoy the social interactions at school. Now, he misses his friends. One week after schools closed last March, the students received an envelope with instructions on how to do their lessons. But Caio does not have internet. The family had one tablet computer. Once the tablet broke, the family lacked the money to repair it. Simone has the family’s only phone, and she takes it with her to work.

At first, Caio tried to keep up with the other students using workbooks. But he grew frustrated by the amount of work and the piles of books he was meant to finish alone without support or supervision. During the lockdown, Caio has fallen further behind in his education. He wants to drop out of school entirely.

But there are bright spots to Caio’s day. Most days, he walks to another favela, Bairro Novo, to visit his grandmother. There he has lunch with his grandparents and his uncle. He goes fishing, and the fish he catches with his grandmother provide sustenance for the family.

The local football league was suspended, but there are informal “pick up” matches in the favela. Caio flies his kite, watching it rise higher and higher into the air: free in a way that Caio wants to be.

His bicycle is his most prized possession – here, Caio finds the true freedom he yearns for. He goes for long rides in the palm-tree-fringed fields near his home, but lately he is finding his bike rides “boring and predictable.” In the pandemic world, Caio must create is learning new pathways to adventure.

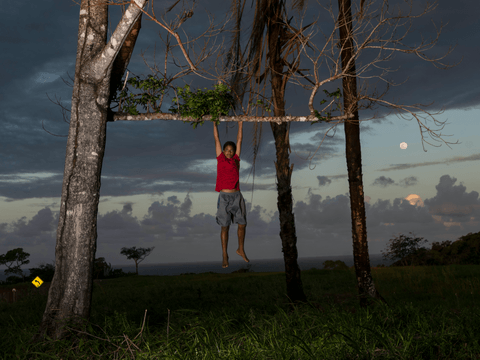

Before the pandemic, he assisted Fernando, a local gardener and maintenance man, doing simple jobs like sweeping pools of holiday homes. But once the authorities began imposing travel restrictions, Bahía’s tourism sector grinded to a halt, leaving hotels and holiday homes vacant. Fernando lost most of his work and could no longer pay Caio. Still, Caio assists him without pay. Caio claims it is a way for him to get out of the house and a break from the monotony of life under lockdown. He also believes it is something he does well. His work with Fernando gives Caio a sense of meaning and pride. Caio dreams of building his own home someday, in the jungle. He already knows how to make a hut because he watched it on TV.

“If we’re supposed to do what we love best, I may need to find a job where I am paid to climb trees.”

About UNICEF’s work for every child

As of March, schools for more than 168 million students had been completely closed for almost an entire year. Latin American and the Caribbean have been disproportionately affected, with 114 million schoolchildren in the region without face-to-face schooling.

UNICEF is committed to getting children like Caio back to in-person learning as soon as possible and ensuring they have the services they need to readjust and catch up after the pandemic. Learn more about how we’re helping here.